Saints and Sinners, the book by Iain Smith and Joan Forrest (recently reviewed), will resonate at many points with anyone who has Lewis connections, setting off multiple memories and associations of ideas, a few of which are explored here.

One of the chapters is about Donald Mackenzie from Aird Point on the Isle of Lewis (1882- 1942), whose mother Janet was unmarried:

"Donald Mackenzie was the

1882 [born] son of a single mother from Aird Point. He successively was:

Dux of the Nicolson Institute; a first class honours graduate and member of staff of the University of Aberdeen; a church minister; and a professor in Princeton Theological Seminary."

- From a transcript of the book launch.

The following is about another single mother, called Janet, in 19th-century Lewis, whose children also thrived and flourished, if rather less spectacularly.

In the 1851 Census -

Janet [a.k.a., later, Jessie]* Morrison was a Seamstress, 19, living at South Beach Lane, SY (Stornoway), with her parents Donald, 47, Blacksmith (Master) from Ness, and Ann, 46, born in SY. Siblings: Peggy, 16; Norman, 14; William, 12; Mary Anne, 10; Roderick, 8; Donald, 6; and Morrison Infant (female) 1 month.

Janet [a.k.a., later, Jessie]* Morrison was a Seamstress, 19, living at South Beach Lane, SY (Stornoway), with her parents Donald, 47, Blacksmith (Master) from Ness, and Ann, 46, born in SY. Siblings: Peggy, 16; Norman, 14; William, 12; Mary Anne, 10; Roderick, 8; Donald, 6; and Morrison Infant (female) 1 month.

Janet

Morrison is listed with her infant daughter

(later recorded as Anne Maciver). Meanwhile, in Findochty, Joe’s paternal

grandmother Catherine Pirie was 22,

unmarried, living in her parents’ home with son Walter James Flett, aged 2

months.

* Saints and Sinners makes mention of someone else interchangeably called Janet or Jessie. It was quite usual for both these names to be used for the same person, with 'Janet' seen as being a shade more 'proper' and official.

* Saints and Sinners makes mention of someone else interchangeably called Janet or Jessie. It was quite usual for both these names to be used for the same person, with 'Janet' seen as being a shade more 'proper' and official.

And in 1851 Roderick Maciver, Blacksmith, (later named as Ann's and Jessie’s father, was 25, unmarried, living in Keith Street, Stornoway, with: his father Donald Maciver, Blacksmith, 51;

mother Flora, 45 (Barvas),

sister Barbara, 13, Scholar, brother John, 8, and House Maid Ann McLennan from Barvas.

This is the latest

year that Roderick Maciver has been identified in the census.

|

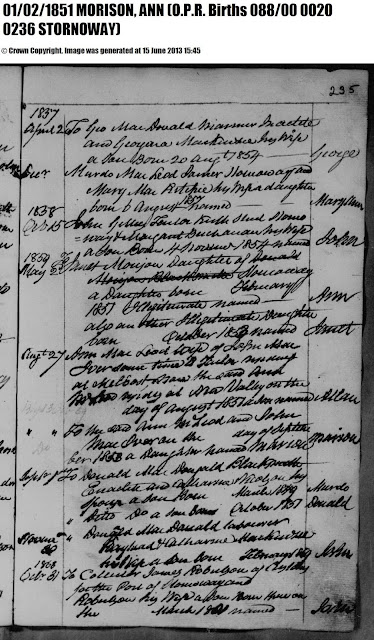

| Scrappy record of 'illegitimate' birth for Ann and her sister Jessie, as Janet (at 1859 [?] May) |

The sisters' births are recorded together in the Old

Parish Register as follows:

[Marginal date May 2 1859*[?] To Janet Morison, Daughter of Donald

Morison, Blacksmith Stornoway, a Daughter born February 1851 Illegitimate named – Ann also another

Illegitimate Daughter born October 1854 [3 changed to 4] named Janet. C

*This may be to do with the “Registers of Neglected

Entries compiled for each parish by the Registrar-General

after statutory registration began in 1855, [which] contain a small number of birth

entries proved to have occurred between 1801 and 1854, but not entered into the

parish registers”.

Mistakes and corrections may indicate that there was some confusion, or be a result of canny obfuscation in the face of official questioning. A similar explanation may apply to censuses.Morison is the older form of Morrison, the latter becoming the more common spelling later.

This

seems to be the only time Janet’s second daughter is called Janet rather

than Jessie, the form that will be used for her in this account. Jessie rather than Ann is highlighted in the following records, because it was her line that was being traced when they were found.

In 1861 Ann(e), 10, and sister Jessie aged 7 were living at Keith Street, Stornoway,

with (maternal) grandfather Donald

Mor[r]ison, Blacksmith, 59; aunt

Margaret, Dressmaker, 22; uncles

Roderick, Ap[prentice] Blacksmith, 18, and Donald, Scholar, 16. All born in SY.

Anne is evidently the Infant of 1851, now clearly Donald’s

grand-daughter (like Jessie), not daughter; both are surnamed Maciver. Their mother (Janet Morrison) was apparently not in the house on the census night, nor was their grandmother Ann who

was presumably still alive in 1866 (not noted as “deceased” on the marriage

register below).

In all subsequent official documents the surname until they married, then 'maiden surname' (m.s.) of Ann and Jessie is given as Maciver/McIver, and where required their father's name is given as Roderick Maciver/McIver. As noted above (1851 and 1841 census) he has been provisionally identified as Roderick Maciver, Blacksmith (son of a near neighbour of Donald Morrison and fellow blacksmith), who was a few years older than Janet Morrison. His disappearance from later records is as yet unexplained. It is in theory possible that he lent his surname through friendship or by inter-family arrangement; in any case, it looks as though his father willingly accepted the grand-paternal role and the families stayed close.

There were, however, rumours transmitted to later generations that the paternity of one or both of the girls was not so simple, with mention of an exotic, possibly oriental connection via 'an officer off a boat'. This is scarcely borne out by the appearance (where known) of Jessie and her children at least, and may have been an effect of scandal and gossip. Notwithstanding her consistent use of the surname Maciver, Jessie brought up her children to take a pride in the Morrison connection.

'Saints and Sinners' has a chapter on Stornoway-born Robert Mor(r)ison Maciver, 1882-1970, who became an eminent sociologist. There is, however, unlikely to be any relationship with the above Morrisons and Macivers - both surnames are common enough on the island.

In all subsequent official documents the surname until they married, then 'maiden surname' (m.s.) of Ann and Jessie is given as Maciver/McIver, and where required their father's name is given as Roderick Maciver/McIver. As noted above (1851 and 1841 census) he has been provisionally identified as Roderick Maciver, Blacksmith (son of a near neighbour of Donald Morrison and fellow blacksmith), who was a few years older than Janet Morrison. His disappearance from later records is as yet unexplained. It is in theory possible that he lent his surname through friendship or by inter-family arrangement; in any case, it looks as though his father willingly accepted the grand-paternal role and the families stayed close.

There were, however, rumours transmitted to later generations that the paternity of one or both of the girls was not so simple, with mention of an exotic, possibly oriental connection via 'an officer off a boat'. This is scarcely borne out by the appearance (where known) of Jessie and her children at least, and may have been an effect of scandal and gossip. Notwithstanding her consistent use of the surname Maciver, Jessie brought up her children to take a pride in the Morrison connection.

'Saints and Sinners' has a chapter on Stornoway-born Robert Mor(r)ison Maciver, 1882-1970, who became an eminent sociologist. There is, however, unlikely to be any relationship with the above Morrisons and Macivers - both surnames are common enough on the island.

In 1866 Janet, as "Jessie Morrison, spinster", got married, not to the named father of her two girls:

Murdo Nicolson, Tailor, 26, m. Jessie Morrison, 33, Spinster, 13-7-1866, at Crossbost, Lochs, ”After banns according to the forms of the Free Church of Scotland.” Address: Stornoway (both). Parents: John Nicolson, Fisherman, and Isabella, m.s. McLeod; Donald Morrison, Blacksmith, and Ann, m.s. Murray.

Census. In 1871 Anne McIver was a Pupil Teacher*, aged 18; Jessie McIver aged 16 was still at school, living at 12 Keith Street , SY, with her stepfather Murdo Nicolson, Genl. Mercht. Tailor & Clothier; mother Jessie Nicolson [Janet Morriosn that was] ; half-sister Christina A Nicolson, aged 2, and half-brother Murdo A Nicolson, less than 1 year old.

[n.b. Civil Parish and Address incorrectly listed as Stronoway on the Find-my-past transcription].

Anne and Jessie were being educated past the minimum school leaving age, indicating both that they had some aptitude for learning and that the family was not desperate for them to start earning.

*'Saints and Sinners' has information on Pupil Teachers, in the context of education in Stornoway.

[n.b. Civil Parish and Address incorrectly listed as Stronoway on the Find-my-past transcription].

Anne and Jessie were being educated past the minimum school leaving age, indicating both that they had some aptitude for learning and that the family was not desperate for them to start earning.

*'Saints and Sinners' has information on Pupil Teachers, in the context of education in Stornoway.

|

| Ann married a fellow teacher and emigrated. Her (putative) paternal grandfather was a witness at the wedding. |

In the spring of 1881 Jessie McIver (24*) was a Saleswoman,

living at 27 Bayhead, Stornoway, with her stepfather Murdo Nicolson, General

Merchant; mother Janet

Nicolson; half-brother Murdo A Nicolson, 10; and Nicolson half-sisters

Christinia (Christina) A, aged 12; Johanna M, 8; and Janet (Janetta) J, 5. Servant

Christinia Murray, 22, from “Barras” [Barvas]. Family birthplaces Lochs or Stornoway.

[Several transcription errors evident].

This census recorded the use of Gaelic, which they were all said to speak.

*Ages given in census (and some other) records are notoriously unreliable.

[Several transcription errors evident].

This census recorded the use of Gaelic, which they were all said to speak.

*Ages given in census (and some other) records are notoriously unreliable.

Jessie’s

maternal grandfather Donald Morrison was now a widower, 79, living at 12, Keith Street, Stornoway (the

Nicolsons’ address in 1871) with his unmarried daughter Margt., 45, as House

Keeper.

On 17-8-1881 John Maclean, 29, married Jessie McIver, 26, at Bayhead

Street, Stornoway. John’s address: Point

St. SY; Parents: Lachlan Maclean, Fisherman, and Anne MacLean m.s. Mackay. Jessie’s address: Bayhead Street. Parents: Roderick McIver, Blacksmith (Master) and Janet Morrison, Dress-maker.

The presumption

is that the Roderick McIver named as Jessie’s father was alive in

1881 since he is not described as ‘deceased’ but he appears in the

census only in 1841 and 1851 (with near-certainty). An element of obfuscation may be discerned here too, however, preserving for the record the dual identities of 'Janet Morrison' and 'Jessie Nicolson'.

The marriage lasted until John's death in 1915 and they raised a large family. John Maclean (no relation to the celebrated Glasgow socialist) was a well-known and respected local shopkeeper. Thus neither 'illegitimate daughter' seems to have suffered unduly from this designation in the long term, although one can only guess at what they may have had to put up with as children.

There was, however, enough lingering scandal and notoriety attaching to Janet's name for it to be occasionally 'cast up' to some of Jessie's grandchildren, as in: 'the people you come from' and 'She was a bad woman!'

The marriage lasted until John's death in 1915 and they raised a large family. John Maclean (no relation to the celebrated Glasgow socialist) was a well-known and respected local shopkeeper. Thus neither 'illegitimate daughter' seems to have suffered unduly from this designation in the long term, although one can only guess at what they may have had to put up with as children.

There was, however, enough lingering scandal and notoriety attaching to Janet's name for it to be occasionally 'cast up' to some of Jessie's grandchildren, as in: 'the people you come from' and 'She was a bad woman!'

|

| Jessie in her garden in Stornoway |

After Jessie's death the house and shop passed to her eldest daughter, Mary Anne Morrison Maclean (died 1954).

|

| Stone in Sandwick Old Cemetery: Janet Morison, died 1909, wife of Murdo Nicolson (with her husband and a son who died in infancy) |

|

| Stone in Sandwick Old Cemetery: Jessie Maciver, died 1928, aged 74; with John Maclean and 3 of their children |

in the parish of Rathven, Banff-shire, north-east Scotland...

And (1851) James

Flett, 33, Fish Curer, was Unmarried, living in Victoria Square,

Rathven, with his widowed mother Margaret Flett, [née Smith], Stocking Weaver, Head

of household, and two of her Grandsons, Alexander Smith, 22, Cooper, and

George Smith, 13. All born in Rathven.

So James as well as Catherine is listed ‘Unmarried’ in 1851, each living with parent(s) - their son Walter, 2 months old, was with Catherine but already had his father's surname.

It may look as though two-year-old John Pirie Legg could have been a son of Catherine's unmarried sister Margaret, but there was an older sister:

10 years later -

It may look as though two-year-old John Pirie Legg could have been a son of Catherine's unmarried sister Margaret, but there was an older sister:

In 1841 Katharine Pirie, i.e.Catherine, was 12,

living in Findochty, Rathven with her elder sister Ann Pirie, 15, Spirit Dealer; and younger sisters: Margaret, 9; and Isabella, 6, born in

England (others in Banffshire). Interestingly the teenage Ann appears here as Head of the household (and business) - their parents must have been away visiting or working somewhere

and Ann’s responsible position temporary, given the 1851 record above; note also Isabella's birth-place, 'England'. The occupation of Cooper (barrel-maker) was one of those connected with fish which involved seasonal migration and business in different ports.

In 1861 John 'Perrie' (Pirie) Legg was 13, a scholar, still living with his grandparents (also 'Perrie') and others including his aunt Isabella, none with the surname Legg, in 'Public House', Rathven.

In 1861 John 'Perrie' (Pirie) Legg was 13, a scholar, still living with his grandparents (also 'Perrie') and others including his aunt Isabella, none with the surname Legg, in 'Public House', Rathven.

10 years later -

In 1861 Catherine, Fish Curer's Wife, was 31, married to head of household James Flett, 43, a Fish Curer, living in a Private House, Rathven, with their children: Walter Jas (James), 10; Alexander aged 7, Scholar; Margaret, 5; William D (Downie), 3;

and Catherin[e], 10 months. All born in Rathven. Also Isabella Taylor,

Domestic Servant, 23, and Margaret Flett,

Fisherman's Widow, 84 (James’s mother).

|

| Catherine married James and had several more children. She died in 1868,(her age given as 38), of peritonitis. |

Towards a comparison:-

(There might an interesting research topic or two here..?)

Although the situations of Janet in Stornoway and Catherine in Rathven in 1851 appear alike, Catherine's (and her sister's?) is likely to have been more in keeping with the customs of her community, as was her subsequent course of life. In neither place was the birth of children 'out of wedlock' exactly unheard-of, and there were ways of assimilating such occurrences, with a greater or lesser degree of concealment. For example, when large families were the norm it was quite possible for siblings to be 20 years or more apart in age, so that relationships could be blurred, and there would usually also be an extended network of potential carers if required. Tolerance within the family, when social exclusion of an 'erring daughter' would have been neither desirable nor practical, appears to have been fairly prevalent, general acceptance and acknowledgement in the community at large rather less so.

Where such a situation does seem to have been more readily accepted, tolerance may have been conditional upon the father being known and belonging to the community, and the parents were expected to get married, even if belatedly*. With young men often 'away at the fishing' or 'Away at South' (as listed on censuses) it would not have been possible always to arrange a ceremony in time to maintain ideal respectability. It has even been suggested that the proven ability to reproduce was, in fishing villages on the east coast, seen as a desirable preliminary to the formalities, to ensure a sustainable work-force and therefore economic survival.

*Saints and Sinners includes just the one single mother, but makes a sly allusion to 'short gestation times', i.e. births occurring within rather few months of the parents' wedding.

Postscript:-

In December 1913 a grandson of Catherine (via her second son, Alexander), married a grand-daughter of Janet via Jessie. In due course there were therefore joint great-grandchildren of Janet and Catherine, and so on unto the third and fourth (so far) generations.

(There might an interesting research topic or two here..?)

Although the situations of Janet in Stornoway and Catherine in Rathven in 1851 appear alike, Catherine's (and her sister's?) is likely to have been more in keeping with the customs of her community, as was her subsequent course of life. In neither place was the birth of children 'out of wedlock' exactly unheard-of, and there were ways of assimilating such occurrences, with a greater or lesser degree of concealment. For example, when large families were the norm it was quite possible for siblings to be 20 years or more apart in age, so that relationships could be blurred, and there would usually also be an extended network of potential carers if required. Tolerance within the family, when social exclusion of an 'erring daughter' would have been neither desirable nor practical, appears to have been fairly prevalent, general acceptance and acknowledgement in the community at large rather less so.

Where such a situation does seem to have been more readily accepted, tolerance may have been conditional upon the father being known and belonging to the community, and the parents were expected to get married, even if belatedly*. With young men often 'away at the fishing' or 'Away at South' (as listed on censuses) it would not have been possible always to arrange a ceremony in time to maintain ideal respectability. It has even been suggested that the proven ability to reproduce was, in fishing villages on the east coast, seen as a desirable preliminary to the formalities, to ensure a sustainable work-force and therefore economic survival.

*Saints and Sinners includes just the one single mother, but makes a sly allusion to 'short gestation times', i.e. births occurring within rather few months of the parents' wedding.

Postscript:-

In December 1913 a grandson of Catherine (via her second son, Alexander), married a grand-daughter of Janet via Jessie. In due course there were therefore joint great-grandchildren of Janet and Catherine, and so on unto the third and fourth (so far) generations.