French Nuclear Tests in the Sahara

Notification from the research group “achac”:

Research group ACHAC - Colonisation, immigration,

post-colonialism

"In the context of 'fake news', the photograph titled Reggane 1960 is a perfect

example of the controversies and differing interpretations to which a picture

can give rise. Taken by the French Army in the Algerian desert in December

1960, as part of the Gerboise mission – the first series of French nuclear

tests, carried out in the midst of the Algerian War – it shows two lines of

rigid, unmoving figures tied to stakes. Published in Les années 50. Et si la

guerre froide recommençait ? [The 1950s: What if the Cold War started up

again?] (La Martinière, to be published on 5 April 2018), it is deciphered

here by the three authors of the book, Farid Abdelouahab, art historian, Pascal Blanchard, historian, and Pierre Haski, journalist and President of ‘Reporters

sans frontières’."

Fallout from a Photograph

"This photograph of dummies set up to test the effect of the nuclear blast in the atmosphere gave rise to polemics. It was linked, as evidence, with the story of Algerian "human guinea-pigs" said to have been sent to the (test) site and deliberately irradiated by the French authorities; a news film proves that they are really dummies and not human bodies." [Reggane, Algeria].

Translation from French text, 'Fate of a photograph'

(slightly shortened)

We chose this photograph to illustrate one of the symbols of the Cold War, showing dummies set up by the French Army to test the blast from the explosion. But this picture, like present-day “fake news”, became the image of a crime perpetrated by France, that is the impact of these tests on a civilian population and on French soldiers, but also, according to some people, the “proof” that France had exposed not dummies, but FLN (National Liberation Front) prisoners of war in nuclear radiation tests. […]

On this photograph we see a dozen dummies in military uniform – very diverse and unregimented – set down in the Algerian desert. We ascertained that it should have been dated to the third test, that of 27 December 1960; this is confirmed by film and other archive images. For many years this photograph has featured in accusations brought against the French authorities by representatives of Algerian institutions … demanding acknowledgement of serious matters concerning “crimes against humanity”. In fact it is often used, mainly on the internet, to denounce presumed experiments carried out on 150 Algerian FLN POWs said to have served as ‘guinea-pigs’, in some cases disguised as dummy soldiers and tied to stakes about 1 kilometre from the epicentre in order to inform military scientists about radiation effects. The survivors/remains are supposed to have been taken to France for further research…

The First French

atmospheric tests

To understand this, we need to go back to the early nuclear age… [USA

16-7-1945; USSR 1949; UK 1952}. In 1958 General de Gaulle, on coming to power,

confirmed the order for nuclear weapons experiments and speeded up the

preparations already begun by is predecessors two years earlier, and the

Minister for Defence created a consultative committee tasked with studying the

problems related to nuclear tests. The machine had got going…

In the following years the Operational Group for Nuclear Experimentation

(GOEN) defined security zones. Contemporary military theories from the Warsaw

Pact envisaged the possibility of manœuvres and confrontations with the enemy

in zones contaminated by radioactivity after explosions. In the wake of the

other great powers, the French army during that period doubtless had to take on

board such views.

The Sahara Centre for Military Experimentation (CSEM) in

Reggane began to emerge from the Algerian sand at the end of 1957, in the midst

of the Algerian War, bringing together several thousand civil and military

personnel in the

Tanezrouft region, in a vast complex situated about 40

kilometres from

Hamoudia.

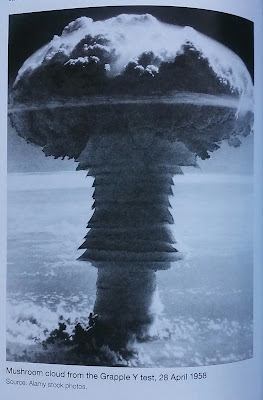

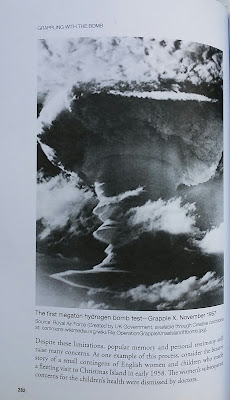

The explosion of 13 February 1960 initiated a series

of four atmospheric tests code-named ‘Gerbils’ – Blue, White, Red and Green (the

gerbil being a small rodent of the desert). They went on until 25 April 1961, a

few days after the generals’ putsch in Algiers.

Launched from the top of a metal tower, the first blast

released energy of the order of four times that of Hiroshima (70 kilotons).

Around point zero, military materiel (aircraft, vehicles…) and also animals

(rabbits, goats, rats) spread about in cages had been placed in order to

analyse the biological effects of the flash and proceed to ophthalmology

experiments. Each test entailed numerous assessments to be made with a view to ascertaining the consequences of the energy release: nuclear diagnostics,

high-speed photography, radiochemical analyses carried out on the particles

collected by aircraft flown inside the radioactive cloud. The zone, in

particular the Touat Valley, contained both sedentary and nomad populations.

Many people would be contaminated by the tests. Like numerous French soldiers

and technicians, most of them in shirt-sleeves and sunglasses, as well as many

Algerian workers, and about twenty journalists present at the site, all of them

subjected to large doses of radiation.

A French Senate report dated 2009 states that, “… the

measures taken at the time were not sufficient to prevent the exposure to

contamination of people who either participated directly in the experiments or

were present in the zones around the explosions. These security measures, first

and foremost did not prevent the occurrence of many technical mishaps during

the preparation for or course of the tests.” (Report n°18 (2009-2010),

Marcel-Pierre Cléach, on behalf of the Commission for Foreign Affairs, 7 October

2009). To sum up, things were not perfect. According to data from the Algerian

League for the Rights of Man, 24,000 civilians and soldiers were directly

exposed. A document declassified in 2013 and made public the following year

highlights the significant duration of the fallout. All these indications

tend to the same conclusion: the impact on the environment and on local

populations was major.

On the day after the first explosion, the radioactive cloud

reached

Tamanrasset and Central Africa then moved up towards West Africa, reaching

Bamako.

Criticism was powerful, but the French media and the services

concerned were to develop counter-propaganda.

Two weeks later, still laden with

radioactivity, it reached the Mediterranean coastlines of Spain and Sicily (Fabienne

Le Moing, « Tribunal administratif : les conséquences des essais

nucléaires en Algérie » [archive], France 3-4 September 2014). Some

radio-isotopes thrown out by the explosion could have been ingested by people

on the ground in spite of being diluted in the atmosphere.

There is no doubt that these radioactive

elements cause cardio-vascular disease and cancers. (Brunot Barillot, « Le

document choc sur la bombe A en Algérie », Le Parisien, 14 February

2014).

Criticism was powerful, but the French media and the services

concerned were to develop counter-propaganda.

Two weeks later, still laden with

radioactivity, it reached the Mediterranean coastlines of Spain and Sicily (Fabienne

Le Moing, « Tribunal administratif : les conséquences des essais

nucléaires en Algérie » [archive], France 3-4 September 2014). Some

radio-isotopes thrown out by the explosion could have been ingested by people

on the ground in spite of being diluted in the atmosphere.

There is no doubt that these radioactive

elements cause cardio-vascular disease and cancers. (Brunot Barillot, « Le

document choc sur la bombe A en Algérie », Le Parisien, 14 February

2014).

This is all known and acknowledged today but it is necessary to proceed

with the story as it relates to the famous photograph.

The second explosion, much less powerful (4 kilotons) was

carried out on 1st April 1960 during the official visit of Nikita Khrushchev to France (23 March to 3 April 1960), and Gaumont news announced

that “France, for its part, wished to demonstrate, at Reggane, that its

inclusion in Nuclear Club was not simply a matter of form”. The means of detonation and measurement were

installed in barracks and the bomb was placed on a platform at ground level

(for all the other test, it was placed in shelter at the top of a hundred-metre-tall

tower, later a smaller one of 50 metres). (Pierre Billaud (Direction), La

grande aventure du nucléaire militaire français. Des acteurs témoignent, Paris,

L’Harmattan, 2016). The explosion set off a fireball more than 100 metres in

diameter going up to 280 metres above the ground.

For the third atmospheric test of 27 December 1960 several

hundred animals and military materiel as before, but along with dummies dressed

in uniform (supplied with radiation receptors according to some sources), were

placed at various distances around ground zero, situated 15 kilometres from the

command post. The two tests, with two different dates, are central to the mistake

made about the photograph, this is why the facts are important.

As can be verified in a news programme of the time (Gaumont News,

December 1960, Reference 6101GJ 00006), those figures held up by iron bars are

certainly made of cloth and cannot contain human bodies, dead or alive. They

are the same dummies which are to be found on the photograph we published in

our book (so dated December 1960), and which subsequently illustrated articles

denouncing the use of human guinea-pigs in tests for radioactivity… but

locating the event in April 1960.

But the image is powerfully symbolic and invokes the

violence of the Algerian war and those terrible years. This is why it is re-invoked

regularly. A narrative now emerges about the use of Algerian prisoners who were allegedly

deliberately contaminated and this picture has become the most obvious symbol

or even ‘proof’, given its composition and the violence it illustrates in such a

situation. No-one really sets out to seek its real context, nor to find the

other pictures or film relating to the event. Then conflation begins. The arrival

of the dummies - which can be checked on other photos (like one from the archives

of l’Établissement de Communication et de Production Audiovisuelle de la

Défense, Réf.: F 60-20 R651) - is as if non-existent; no-one has looked for the

images or they have failed to find them. The Gaumont film archives or those of the

army are forgotten. In this respect too, no-one has pursued the investigation

to its conclusion.

In the course of the fourth blast, Operation Green Gerbil –

a failed test since its power was no more than 1 kiloton, whereas it was initially

estimated at between 6 and 18 kilotons – ‘tactical exercises in the nuclear environment’

[blog ref. supplied] did take place. Operations involving about a hundred troops:

helicopters, armoured vehicles, and infantry provided with protective equipment undertook

reconnaissance in the contaminated area. Nearly 200 soldiers were involved

after the blast, in exercises which put them within 650 and 300 metres of

ground zero for several hours. Showers were their only means of decontamination.

The Parliamentary Office for Evaluation of Scientific and Technical Choices Report,

2001, indicates 42 cases of skin contamination among personnel in the test

area. The obvious, known shocking thing is this above all – the contamination

of soldiers and civilian populations in all the tests – but the polemic citing

the image as evidence persists; on the contrary, the ‘fake news’ becomes more

significant, copied form one site to another. It makes people forget the

central evil and most importantly this photograph is taken as proof, when a

genuine investigation should be undertaken on the use of guinea-pigs during the

Algerian War.

This

question is even more important today since in early 2018 the French Constitutional

Council reviewed all the traumas suffered by civil populations and decided that

Algerian civilians who had sustained physical damage from violence attributable

to the conflict could now claim pensions paid by France. The Constitutional Council

removed the words ‘of French nationality’ which until then had restricted these

benefits to victims of the ‘Hexagon’ [‘casual synonym for the mainland part of

Metropolitan France’] only, invoking the principle of ‘equality before the law’

guaranteed by the Constitution. From now on, Reggane can be included in an

extensive set of questions about possible compensation for populations affected

at the time. It is therefore a major subject and investigation of provable and

alleged facts must be resumed.

Where did the myth

around this photograph come from?

It was natural enough that the French authorities always

disputed the secondary effects of Reggane: “There was never any deliberate

exposure of local populations,” a Ministry of Defence spokesman asserted in 2007…

“Only dead bodies were used to study the bomb’s effects,” he added. Such a

statement only added to the controversy, and gave support to those who thought

that France had committed a crime at Reggane. Acknowledging that cadavers had

been used left room for further doubts. And what bodies were involved? Might

it be new evidence that living people had been exposed at Reggane in December

1960?

To reopen this question is also to investigate a state

secret, relating to the pact concluded between Paris and Algiers allowing France

to continue its experiments after independence until the site was dismantled in

1965. It explains the silence of the Algerian regime (or at least the complex

twists of history writing) which, under military influence, has until the last

few years made little use of the tests in anti-French propaganda or

critiques. So it was human rights organisations that took up the fight on this

issue and took the “Reggane dummies” as an icon of their struggle, a just one insofar

as it concerned their quest for knowledge, but based on a misleading image.

In fact, numerous recent studies have shown that the populations

of Reggane and of Eker in Tamanrasset are still suffering the effects of those

tests, which have cost the lives of thousands of people and led to serious

illnesses. At Reggane, where the tests were atmospheric and covered a vast unprotected

area, doctors say that exposure to ionising radiation has caused more than 20

types of cancer. Before the tests, cereals and dates were grown there, and

there were various types of animal. That has all gone.

This major ecological crisis is part of the historical

record. Attention turned to the testimony of a Legionary said to have taken

part in the assembling of 150 prisoners in March 1960 – this was taken up very

quickly by the Algerian league for the Rights of Man – a fact reported by a

hero of anticolonialism, the unassailable cinéaste René Vautier. In fact Vautier, who was then working on his

film Algérie en flames (Algeria in Flames), seems to have been told this

story by another director, Karl Gass – second hand testimony, never repeated,

but for many this was taken as irrefutable proof.

Then the Canard enchaîné published photos in a

dossier. Forensic doctors validated the photographs. There was talk of many others,

but they were never seen. There was talk of numerous witness statements showing

that the prisons had been cleared of 150 prisoners by the French Army and these taken

on to the Reggane site. From here on, no-one saw dummies any more, but human

bodies wrapped in clothes. This photograph had to be the missing piece of

evidence, to influence opinion. Actually, it was a false trail and the

investigation stalled.

Witnesses mixed up dates and evidence. What did it matter if

the “150 Prisoners” business dated from March-April 1960 and the photograph

from December 1960? It became an icon, pictorial proof. Witnesses like a doctor

from El Harrach hospital confirmed the facts. Some people began to denounce the

secret clauses of the Évian accords regarding the tests, negotiated in 1961-62…

The FLN had agreed that France could use the Saharan sites for nuclear,

chemical and ballistic tests for 5 more years. So the French could not be held to account, then

or now.

In Algeria, the lawyer Fatima Ben Braham stated: “A study of

certain photographs enables us to affirm that the position of the so-called

dummies is oddly like that of human bodies wrapped in clothing. Besides that, a

number of Algerians detained in the west of the country and sentenced to death

by special tribunals of the [French] army have contributed illuminating

testimony. Some of those sentenced to death were not executed in prison, but

were transferred and never seen again. They were said to have been handed over

to the army. Research in the registers of judicial executions yields no trace

of their executions, still less of their release. The same fate was reserved

for other individuals interned in the concentration camps.” But those

testimonies are neither published nor verifiable. [... A couple of other examples.]

It all tends in the same direction. Still, there is

confusion over facts, evidence and dates, on several levels. There are the

facts – what happened at Reggane during the Algerian War, in the midst of

unlimited violence? There are witness statements and evidence, their value impossible

to assess. And there is the photograph, which has become 'the' definitive proof.

Of course this does not mean that the alleged crime has no basis in fact, but

it does mean that a photograph has a history and cannot be taken as evidence

without being examined.

The picture actually recounts another story, about France in

Algeria during and after the war, with a total of 11 tests carried out after

independence, up to February 1966, tested its bomb, in the process contaminating

with no shadow of doubt French soldiers, scientists, and thousands of

civilians. A government which has no doubt made experiments on bodies, living

or dead, as the then spokesman of the MoD, Jean-François Bureau, rashly acknowledged

in 2007. But the investigation is still at an early stage.

All this now requires in-depth study. Improper use of the

picture involved is stopping us from getting at the truth. A mistake which has

become typical of our time: claiming without proof, affirming without

investigating, favouring ‘fake news’ over thorough research. It is the role of

historians and journalists to question facts and images and go beyond

appearances to try to understand what really happened at Reggane. In 1960. In

the middle of the Cold War. In the nuclear arms race. Pictures tell us about

history and can make history, but like facts they need contextualisation,

analysis and validation.

=======================

Previously on this blog: